After a decade defined by a swelling death toll, the rate at which Baltimoreans are dying of overdoses may be slowing — a national phenomenon that’s given hope amid a devastating crisis.

Baltimore saw 566 fatal overdose deaths as of September, according to preliminary data from the Maryland Department of Health. While a myriad of preventable deaths remain, the number puts the city on track to possibly end the year with fewer than 800 deaths, a significant drop compared to recent years.

The last time the city saw less than 800 deaths was in 2017, which preceded a pandemic-era surge in fatalities caused by the proliferation of fentanyl.

“It seems like overdoses are significantly lower this year than last year or other recent years, particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic,” said Kenny Feder, assistant research professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health’s Department of Mental Health.

“And it’s not just a Baltimore phenomenon.”

Last year, the country’s fatal overdose numbers decreased for the first time in five years, though Baltimore’s increased by 5.5% — marking a death toll of more than 1,000.

Now, however, Baltimore seems to be catching up as the decline becomes more significant.

The rebound comes after a “tragically high” surge in deaths that was worse than many thought was possible, Feder said. As extremely potent synthetic opioids rocked the drug market, deaths in Baltimore peaked in 2021, when the state reported 1,079 deaths.

Three years later, although the numbers are still relatively high — particularly in comparison to pre-pandemic levels — the new data shows the death rate may have reached its limit as fentanyl became the norm.

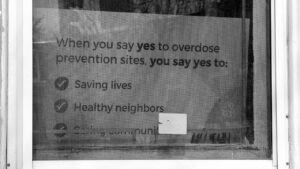

It’s difficult to pinpoint just one reason for the decline, Feder said, although it seems to indicate that harm reduction initiatives are working.

Cities such as Baltimore have perhaps most importantly ramped up the distribution of naloxone, an opioid antagonist that is at the crux of strategies to prevent fatal overdoses.

Emergency service personnel administered the life-saving drug, which reverses overdoses, more than 1,600 times in Baltimore this year, according to the state health department.

Locally, the city and local harm reduction organizations have augmented their efforts. They’ve offered syringe service programs, or SSPs, as well as other resources such as naloxone distribution and training.

In tandem, they aim to reduce overdoses, prevent the spread of diseases such as HIV and help individuals access treatment, emphasizing a multifaceted approach to addressing the crisis.

“The thing is, those strategies are effective,” Fedder said. “They were effective before overdoses went up as the saturation of fentanyl went up, and we need more of them. It’s really positive we’re seeing overdoses going down, and those strategies are still saving lives.”